Over the past week, the problem of short, “arranged” draws between top level chess players has reared its head again. Most infamously, perhaps, in the tilt between Magnus and Hikaru Nakamura at the end of the qualifying rounds of the “Magnus Carlsen Invitational,” which featured a “Double Bongcloud”:

e4 e5 2. Ke2 Ke7 3. Ke1 Ke8 4. Ke2 Ke7 5. Ke1 Ke8 6. Ke2 Ke7 1/2 - 1/2 drawn by threefold repetition.

No doubt Magnus was simply tired of recalling the “drawing line,” in the Berlin Defence, which occurred over and over again as top players who had guaranteed themselves a qualifying spot into the knockout rounds early in the qualifying tournament elected to save their energy and fight another day:

e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Nxe4 5. d4 Nd6 6. dxe5!? Nxb5 7. a4 Nbd4 8. Nxd4 Nxd4 9. Qxd4 d5 10. exd6 Qxd6 11. Qe4+ Qe6 12. Qd4 Qd6 13. Qe4+ Qe6 14. Qd4 Qd6 1/2 - 1/2

You might recognize this game as Nakamura - Giri from Rd. 11, Vachier-Lagrave vs. Nakamura from Rd. 13, Nakamura - Firouzja from Rd. 14, or Firouzja - Van Foreest from Rd. 15. Indeed you might recognize it from other rounds and players, or events. It’s a pox on the game of top level chess that disappoints spectators around the world, at least if they had tuned in to see top level players attempt to actually beat each other.

It may come as a surprise to some newer chess enthusiasts, drawn to the game during the coronavirus pandemic or in the wake of the Netflix Original Series, “Queen’s Gambit,” that chess players do like to conserve energy when they can. It turns out that chess is a grueling endurance sport, in as much as it is a battle of wits. And truly, it’s too easy to sit here behind my keyboard and criticize top level GM’s who are merely saving their energy for a later round in the event, one that might actually matter, at that, since they’ve already scored well enough to guarantee that they’ll advance through to the knockout rounds. Really, who cares?

(The Berlin Wall - post-Kramnik)

But then, there’s the issue of the Berlin Defence itself, which for over 20 years, now, has enjoyed the reputation of being “drawish,” and single-handedly dented the popularity of 1. e4, which Bobby Fischer once deemed, “best by test.” When faced with 3. … Nf6, in lieu of “Morphy’s move,” 3. … a6, players with the white pieces have started avoiding the main line, which leads to the “Berlin Endgame,” after

e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Nxe4 5. d4 Nd6 6. Bxc6 dxc6 7. dxe5 Nf5 8. Qxd8 Kxd8 (diagram)

On a relatively recent stream covering Hikaru’s OTB performance on his own channel, Levy Rozman could be heard explaining for the benefit of the audience, “The philosophy behind this is that, for Hikaru, with perfect play the game is a draw. That’s why you see at the top level, especially with the black pieces, all the Berlins.” (I’m paraphrasing, but we’re in the ball park)

Even beginners and newcomers to the game can see that the queens have come off the board as early as move 8. But is that all there is to say about this position? It’s actually fantastically unbalanced. The black player has lost the right to castle, ruined the structure of his queenside pawn majority, and moved the f5 knight 4 times in the first 8 moves. In fact, that knight is rather likely to move again - usually to g6 via e7. In contrast, the white player has a safely castled king, a healthy kingside majority, and a bit of a lead in development. He’s going to gain another tempo or two as the black king attempts to sort itself out, and it’s not so easy for black to find excellent squares for all his pieces. We do know that it’s desirable to have the bishop pair on the open board, and for his troubles, the black player has at least achieved this much. Was it worth it?

For basically 100 years, the chess world thought this question had been answered. “No,” was the resounding chorus. The Berlin endgame is simply bad for black, as Fischer ably demonstrated against Bisguier in the 1963 USA Championship, held in New York:

e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Nxe4 5. d4 Nd6 6. Bxc6 dxc6 7. dxe5 Nf5 8. Qxd8 Kxd8 9. Nc3 Ke8 10. Ne2!? Be6 11. Nf4 Bd5 12. Nxd5 cxd5 13. g4 Ne7 14. Bf4 c6 15. Rfe1 Ng6 16. Bg3 Bc5 17. c3 Nf8 18. b4 Bb6 19. Kg2 Ne6 20. Nh4 h5 21. h3 hxg4 22. hxg4 g6 23. Rh1 (diagram)

This is quite a famous game, and because Fischer won it, perhaps it reinforced the idea that the ending is just not great for the player with the black pieces. To reach this position, Bisguier had already improved on a previous game won by Svetoszar Gligoric, over Neikirkh in the 1958 Portoroz Interzonal. In that game, Neikirkh had over-extended himself with 14. … c5?! and Gligoric made him pay with pressure along the d-file. The issue Neikirkh ran into was simple: black can’t play 0-0-0, because he’s already moved the king, and as a result, he’s a few tempi shy of being able to adequately reinforce d5. Bisguier’s move, 14. … c6 was well motivated, and much better. Fischer must have known that he didn’t get as much from the opening as Gligoric had, but he pressed on anyway, and here, in this exact position, Bisguier went awry.

White has played 23. Rh1 with the intent of playing 24. f4. The f-pawn cannot advance before Rh1 is played, without leaving the h4 knight in the lurch (one feature of the Berlin defence is that, should white attempt to use his kingside majority, black can open the h-file with … h5 and claim that his h8 rook is well developed where it is. Who says black is behind in tempi?). 23. f4? Nxf4! 24. Bxf4 Rxh4 and white is losing the game. But after 23. Rh1, 23. … Kd7 is fine for black, connecting the rooks, and black is well coordinated. If 24. f4?! it’s white, rather than black who’s overextended, and 24. … a5! seems to offer the black player excellent chances:

Instead, Bisguier seems to have been beguiled by Fischer, and he played the poor move, 23. … Bd8 (diagram), which allows Fischer to improve his position with a little tactic, taking advantage of the fact that Bisguier’s rooks are uncoordinated for the time being.

White to play and win … well, white to play and improve his pieces - Fischer did not miss his chance.

Nf5! Rxh1 25. Nd6+ Kf8 26. Rxh1 b5 (diagram)

In this position, it’s clear that white is simply winning. The h4 knight has made it all the way to a secure outpost in d6, white has control of the h-file, and the kingside majority will prove to be more mobile than black’s queenside pawns. The game came swiftly to its conclusion:

f4 Kg8 28. f5 Nf8 29. e6 f6 30. Nf7 Be7 31. Bf4 g5 32. Bd6 Re8 33. Bxe7 Rxe7 34. Nd8 Re8 35. Nxc6 Nxe6 36. fxe6 Rxe6 37. Nxa7 resigns 1-0

That Neikirkh was overmatched against Gligoric (and Bisguier was overmatched against Fischer) is beside the point. These great masters had shown us the way, and the Berlin was not it. The e5 pawn is annoying to play around, white’s kingside majority is more mobile, and the ending is bad for the black player. That was the way for the next 30 years. In 1999, only 25 games were played between 2600+ opponents in the “Berlin,” and 7 of those occurred because Leko preferred the ancient variation 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Bc5!?, not because the Berlin ending had yet been able to repair its reputation. In contrast, in the year 2015, over 160 games played between 2600+ players would start with the moves, 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6, and the reputation of the Berlin as a drawing weapon was already well entrenched. What changed?

Simply, Kramnik wrested the World Championship from Kasparov in the year 2000 with the Berlin Defence, and the chess world took note. Kasparov tried three times to prove an advantage against Kramnik’s Berlin Defence and failed each time. Kramnik achieved three draws. The fourth time it appeared on the board, the players played 14 half-hearted moves and agreed to a draw. In the second game, Kasparov pressed as hard as he could, and nearly broke through. After 39 moves, with 1 move to go before the time control, the players had reached the following position:

Kasparov played 40. f7! temporarily sacrificing the exchange, 40. … Nxf2 41. Re8+ Kd7 42. Rxf8 Ke7 43. Rc8 Kxf7 44. Rxc7+ Ke6 45. Be3 Nd1 46. Bxb6 c3, but the black c3 pawn offers black just enough counterplay to keep the game level.

In the third Berlin game, the players agreed it was drawn after white’s 33rd move, in the following position:

If these positions look like full-blooded, imbalanced chess positions to you, you’re not alone. Short draws are not the fault of the Berlin Defence, they’re the fault of players who lack the creativity to look for holes in their opponent’s preparation and the fault of top Grandmasters too keen to outsource their opening preparations to Stockfish. In actual fact, whether the objective “evaluation” of the top engines is +0.2 or dead equal, =0.00, the Berlin produces fantastically complicated positions, and requires precision from players on both sides. That Kramnik was able to contain Kasparov for three games in the Berlin was a lot more surprising in the year 2000, when Kramnik’s legacy in the chess world was, as yet, unknown. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that Kramnik is one of the greatest ever to play the game, and a rightful heir to the chess throne in his own right. Of course, his preparation was excellent, but it must be said - so was his PLAY.

In modern chess, the top guys are simply too quick to give in to opponents who essay the Berlin Defence. They are too quick to conclude that their opponent is well “booked up” with the latest drawing lines Stockfish has produced, and too reticent to force their opponent’s to remember them. They’re too scared of over-extending (like Fischer nearly did against Bisguier) to risk posing their opponent’s any problems, and they’re too happy with short, arranged draws to help #growthegame of chess in the age of e-Sports. But who will take up the mantle, and actually try to prove something in the principled, main line of the Berlin Defence? This week, it was Candidates’ Tournament hopeful Ian Nepomniatchi who dared to remind the world that the Berlin is not an automatic draw:

Game of the Week #24:

Ian Nepomniatchi vs. Hikaru Nakamura, 1-0, Magnus Carlsen Invitational - Knockout Stages, Rd. 1

e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. 0-0 Nxe4 5. d4 Nd6 6. Bxc6 dxc6 7. dxe5 Nf5 8. Qxd8 Kxd8 9. Nc3 Ke8 (9. … Bd7 is the variation Kramnik had prepared for Kasparov) 10. h3 Be6 11. g4 Ne7 12. Nd4 Bd7 13. f4 h5 14. f5 hxg4 (diagram)

In my database, which, admittedly, is not kept up to date, this position had been reached 4 times in top level games. In all of them, white recaptured automatically, 15. hxg4. In a recent, excellent video covering this game Daniel King mentioned that as of today, 25 games in his database had reached this position. In all of those, white had recaptured automatically, with 15. hxg4. Nepo had prepared something else:

e6!?

Ignoring, for the time being, black’s demonstrations on the kingside.

… fxe6 16. fxe6 Bc8 17. Bg5 gxh3 18. Kh2!? (diagram)

Here, the computers think this position is playable for white. Perhaps even equal. Of course, they prefer 15. hxg4, which offers white a slight but uncomplicated advantage. But Nepomniatchi has played ambitiously - sacrificing two pawns, at least temporarily, to slow down black’s development. The d7 bishop has been forced to retreat to c8, and will need two more moves to escape along the a6-c8 diagonal. Crucially, Nakamura decided to open the f-file by exchanging pawns with 15. … fxe6. It’s unclear, but it might have been better to simply retreat the bishop to c8 straight away, with the “point” that an eventual exf7 Kxf7 would at least rid black of the annoying e6 pawn.

In the diagram position, black would still like to rid himself of the e6 pawn, but it’s not so easy. 18. … c5, intending to push the knight and play … Bxe6 runs into 19. Ndb5! with an instantaneous disaster incoming on c7. 18. … a6 is a bit slow, allowing white to play 19. Rae1, after which e6 is not really threatened in any line. By process of elimination, it seems, one could arrive at the computer suggestion 18. … b6, which aims to develop the c8 bishop to a6, the a8 rook to d8, and start a counterattack against the exposed white king. Nakamura, instead, tried to improve his f8 bishop. Perhaps well motivated, but he must have simply misevaluated the resulting positions. Unfortunately for Naka, white is able to completely dominate the f8 bishop, and prevent it from ever achieving any meaningful activity.

… Ng6?! (intending, perhaps, 19. … Bd6+)

Ne4 (good, and straightforward. If Nakamura carries through with 19. … Bd6+ 20. Nxd6 cxd6 21. Rf7 looks crushing for white)

… Rh5 20. Rg1! (diagram)

Nepomniatchi has simply defended g5, preventing 20. … Bd6+ by allowing 21. Nxd6 cxd6 22. Nf5! with threats to both d6 and g7. Here, Nakamura loses the plot. With his Bd6+ plan having been thoroughly foiled, he goes back to the idea of playing … c5 and … Bxe6. But first - Nb5 must be prevented.

… a6?! (Simply too slow, black has mixed plans and missed his chance.)

Rad1! (looking, perhaps, to give checkmate on d8 if the knight would just get out of the way) Ne7 22. Rdf1! c5? (diagram)

White to play and win.

Nepomniatchi finished off this game in style:

Rxf8! resigns 1-0.

Nakamura simply resigned rather than allow 23. … Kxf8 24. Bxe7 Kxe7 25. Rxg7+ Kf8 26. Rf7+ Kg8 27. Nf6+ with an eventual mate, or 24. … Kg8 25. Nf6+ Kh8 26. Nxh5 when white has won a couple of pieces for his troubles.

Of course, Nakamura could have played differently. But one does wonder if this game will be something of a turning point for chess fans and spectators in terms of the relationship between the top players and the Berlin Defence. In modern chess, computer preparation is just as likely to elucidate really devilish traps and tactics in slightly “inferior” lines like 15. e6!? as it is to find easy equality for black. Dubov in particular has showed an aptitude for looking beyond the “evaluation” of 0.00 and finding the intrigue in non-standard positions, or even objectively “inferior” lines. In this brave, new world, the Berlin might not retain it’s reputation as black’s easiest path to a draw. With neural networks powering today’s engines, it’s no longer so difficult for Stockfish and co. to digest the intricacies of the Berlin, and it’s certainly the case that the black player must play with precision if they don’t want to fall ignominiously into a disastrous ending, like Nakamura, and Bisguier before him.

One can hope, anyway.

Puzzle of the Week #26:

But first, a solution to last week’s puzzle:

Qxe5? is a disastrous, greedy move that runs into immediate difficulty. 1. … Bb4+ 2. Nd2 Rd8 3. Be3 Qc8 4. Bd4? Qc4! 5. Kf2 Qe2+ 6. Kg3 Bd6 and my opponent resigned. 2. Kd1 might be a more stubborn try, but 2. … Qd8+ and black is winning back the sacrificed material, plus interest.

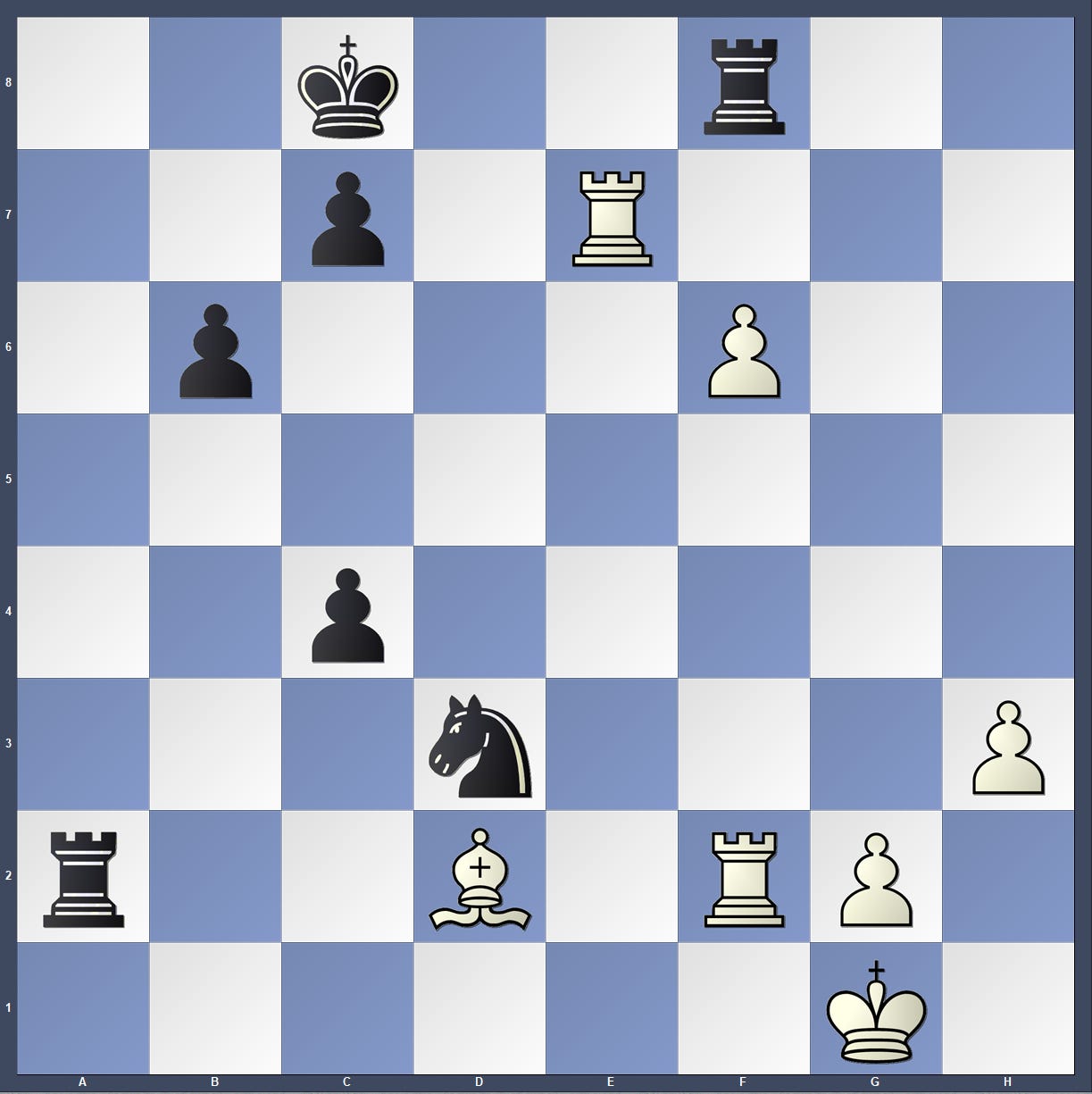

This week’s puzzle is a position that might have occurred, but didn’t quite, in the game Stahlberg - Rojahn, played in Buenos Aires in 1939:

White to play and win.

As always, if you think you have a solution, feel free to shoot me an email at JensenUVA@gmail.com, or DM on twitter @JensenUVA. If you like reading these, feel free to hit subscribe, and you’ll get them directly to your inbox (doesn’t cost a thing). If you know somebody else who might like them - do me a solid and forward it along. It’s always nice to hear from fans.

Great post!