T-S-M! T-S-M! T-S-M!

@GMHikaru shares first place with Magnus Carlsen at the Champions Showdown: Chess 9LX event

The chess world was treated to its first “T-S-M!” chant over the past weekend, when Team SoloMid’s first signed professional chess player, the American Hikaru Nakamura, shared first place with classical world champion Magnus Carlsen at the 2020 “Champions Showdown: Chess 9LX” event, held online and broadcast by the St. Louis Chess Club.

That a chess player has signed with a professional e-Sports team is hardly surprising, given the growth of e-Sports and the emergence of chess as a formidable competitor for the attention of Twitch audiences in 2020. But clearly, the chess world isn’t used to it. During the post-tournament interview, Hikaru tried to start the chant and laughed, while Maurice Ashley (GM and color commentator) stared, dumbfounded. “That’s like, your sponsor?” he asked. Maybe the confusion results from a relative lack of top-level team competitions in chess. Outside of the Olympiad, only the German Bundesliga has historically attracted top chess players. Since 2016, the PRO Chess League has emerged as a terrific online competition, but always took a back seat to over-the-board play. Now that all competitions are online - well... It remains to be seen whether TSM will round out a roster of chess players and enter the PRO league next year. This year, Hikaru has been playing for the New York Marshalls.

Over the weekend, he was playing for himself. The 2020 “Champions Showdown” was a Chess 9LX (Chess 960 if you prefer a consistent application of arabic numerals, or “Fischer Random” for the traditionalists) event that featured reigning classical world champion, Magnus Carlsen, the reigning 9LX world champion, Wesley So, the e-Sports star Hikaru Nakamura, former world champion and political activist Garry Kasparov, top GM’s Fabiano Caruana, Levon Aronian, Maxime Vachier-Lagrave, and Peter Svidler, and finally, the 17 year old Iranian prodigy and bullet-chess phenomenon Alireza Firouzja, who is not yet able to play gate-crasher to the worlds’ elite (he scored only 2.5/9 in this event, his first true test against the best of the best).

Chess 9LX, for the uninitiated, is a “variant” of traditional chess that was invented by Bobby Fischer and first described by the former world champion at a 1996 press conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In “Fischer Random,” the pieces are the same as those used in traditional chess, but they are placed on the starting rank in a mirrored, but random configuration. The only restriction is that the king must start between the two rooks. “Castling” in Fischer Random (Or Chess 960/9LX - so named because there are 960 possible starting positions) occurs only when all the squares between the king, rook and their traditional “castled” home squares (g1 and f1 on the kingside, or c1 and d1 on the queenside) are free, and the king and rook have not yet moved. The idea behind the game is to deprive the players of their home brewed opening preparation and place them on unfamiliar terrain from the very first moves. Each player is given a few minutes before the start of the game to ponder the starting position, which is otherwise a total surprise. The players “true” or “natural” chess abilities are, theoretically, put to the test.

In the champions showdown, which provides our “Game of the Week,” the games were played at the brisk time control of 20 minutes per side, with 10 seconds added after every move. The tournament was a 9 round event played over three days from Friday, September 11th, to Sunday, the 13th, and it had its moments for the viewers. There were “mouse slips,” from both Kasparov and Svidler, who were visibly upset to have accidentally dropped pieces on the wrong squares. There were missed opportunities, from Magnus and Hikaru, who each had chances to win the tournament outright. And there was new blood, in the form of 17 year old, Alireza Firouzja, who struggled, scoring 2 wins, 1 draw, and 6 losses over the 9 round event. One of those wins, marred as it was by mistakes from both sides, seemed like an unusually instructive and “human” game to me - so I’ve reproduced it here, as our “Game of the Week:”

Game of the Week #4

Vachier-Lagrave vs. Firouzja (Champions Showdown: Chess9LX Rd.5) 0-1

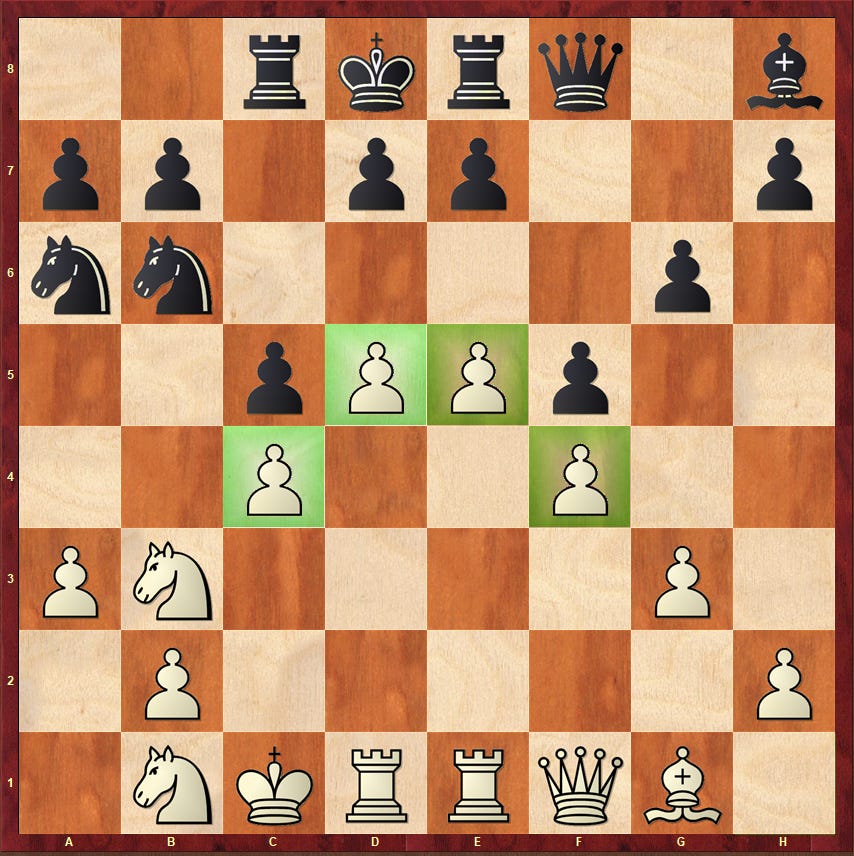

Every game of Chess 9LX begins with a starting position. The starting position for games played in round 5 was as follows:

In this 9LX starting position, white’s light squared bishop is already “developed” on the long diagonal, as is black’s dark squared bishop. The opening move 1. g3 or 1. … g6, therefore, exposes an attack on the opponent’s undefended “b” pawn. There are two undefended pawns in each player’s starting position, the “a” and “b” pawns (compare this state of affairs with the “normal” chess starting position, where only the f7 pawn is weak, defended only by the king). It is important to note that both players are already prepared to castle queenside (!), which can be accomplished from this position simply by swapping the position of the king and rook. The major pieces are already placed aggressively, supporting central pawns on the c-, e-, and f- files (or the d-file after castling) and preparing them for an inevitable central thrust. Moves like 1. c4, 1. d4, or 1. e4 would signal an intent to play classically, developing a formidable pawn center and gaining space, while opening with moves like 1. f4 or 1. g3 also come into consideration for those who prefer a “hypermodern” style, allowing the opponent to establish central control, and seeking to undermine that central structure through effective use of the bishops’ long range influence.

Vachier-Lagrave began in classical style, while Firouzja immediately opened the diagonals for his bishops:

Nb3 g6 2. 0-0-0 (!? - only in chess 960 could such a move be played. The King defends the b2 pawn) f5 3. g3 Nc6 4. d4 Nb6 5. f4 Bd5?

But black’s fifth move is already a serious mistake. It’s one thing to allow your opponent to build up a center in the hopes of undermining it, it’s quite another to allow him to develop with tempo, pushing your pieces all over the board and building up a huge space advantage at the same time. After 5. … Bd5? 6. Bxd5 Nxd5 7. c4 the knight is already attacked and forced to move. White threatens 8. d5, hitting the other knight, and eventually, e4! breaking open the center and staking claim to a huge territorial advantage. Perhaps Firouzja was spoiling for a fight, and was dead set on developing the light squared bishop in preparation for opposite side castling, now that white had found a permanent home for his king on the queenside. If that’s the case, 5. … Bxb3 would have been much better, despite ceding the bishop pair. In fact, the other move that comes to mind, 5. … d5!? closes the center and renders the light squared bishop useless, anyway, so it’s even more perplexing that Firouzja didn’t simply trade off the knight and impair white’s queenside pawn structure:

This mistake reminds me of a common beginner’s move in the queen’s gambit, that generally ends in disaster for the player with the black pieces. After 1. d4 d5 2. c4 Nf6?! is already a bad move, because white can exchange on d5 and establish control over the center with a gain of tempo by harassing the knight: 3. cxd5 Nxd5 4. e4:

In our game, Vachier-Lagrave did not miss his opportunity.

Bxd5 Nxd5 7. c4 Nb6 8. d5 Nb4 9. a3 Na6 10. e4 c5 (after 10. … fxe4 white has 11. c5! Still, this might be a better try) 11. e5 and white has already attained a dominant position.

There’s really no two ways about it here, from the diagram, the white player should feel that they have a very good chance to bring home the full point:

Black shuffles his king to safety on b8 (he never did get a chance to castle kingside), and tries to prepare a pawn break that might weaken white’s center. Either … b7-b5 or … g6-g5 would be desirable, but it’s impossible for black to find squares for his pieces. On the other side of the board, white has an easy task. He simply develops his forces to natural squares. The queen stays on the f1-a6 diagonal where it discourages … b5, and the b3 knight comes to f3, where it discourages … g5. Once developed, white is ready to be greedy - he begins to push even further forward:

… d6 12. Nc3 Kc7 13. Nd2 Kb8 14. Nf3 h6 15. Qd3 Nc7 16. Re2 Nd7 17. b4

Here, white threatens to take twice on c5, when the d6 pawn will be pushed to the side, freeing the d5 and e5 pawns to steamroll through black’s position. Black would prefer, in the end, to maintain the d-pawn on d6, so he shuffles the knight to a6, where it aids in the defense of the c5 pawn, and provokes white’s b-pawn to push on to b5. For his part, white now has a crushing space advantage, but must be careful not to allow the entire queenside position to become closed. He must either sacrifice a pawn with b5-b6 to open the b-file at the right moment, or he must advance the a-pawn to ensure that a breakthrough can be made. The space is a nice, abstract advantage, but in time, that advantage must be converted to a concrete threat.

… Na6 18. b5 Nc7 19. e6 Nf6 20. Kc2 (Judging that the e2 rook is more useful than the d1 rook where it already stands, MVL prepares to swing the d1 rook over to the b-file) 20. … Red8 21. b6!?

Vachier-Lagrave chooses the plan with a temporary pawn sacrifice on b6, to open the b-file for his rook. After 20. … Red8, black was “threatening” to play Nce8, removing the knight from c7, and preparing to meet b5-b6 with … a6, closing the queenside. MVL chooses to strike while the iron is still hot, when b6 comes with tempo and forces black to take the bait.

… axb6 22. Rb1

There’s no time for black to waste. As white threatens to simply capture the b6 pawn, black must find a way to gain something in the exchange. In this case, he’d like to undermine the defense of white’s d5 pawn by playing … b5, but how to bring more pieces to bear on the d5 point? Firoujza simply sacrifices a pawn to clear the f5 square for his queen to enter the fray:

… Ne4!? 23. Nxe4 fxe4 24. Rxe4 b5!?

It’s hard to imagine that Firoujza had any better practical try than this plan, beginning with 22. … Ne4!? and culminating in 24. … b5!? Black is being slowly crushed under the weight of white’s space advantage, and his central pawn chain must be undermined and eliminated. For his part, it would seem that Vachier-Lagrave had grown careless by this point in the game. With 25. g4! white can deny the black queen access to f5, and maintain his control over the light squares in the center of the board. The capture 25. cxb5 is inferior, in comparison, as it allows black to strike back in the center and gives him practical chances. In fact, with the full benefit of hindsight, it’s difficult to understand what the white player missed in this position, or what ghost appeared in his calculation to talk him out of 25. g4! As long as white fights to maintain the central pawns on d5 and e6, he will have the better of things. Once those pawns fall, his pieces find themselves loose and uncoordinated.

The game might have continued, for example: 25. g4! h5! (fighting for access to f5 at all costs) 26. g5 Qf5 27. Nh4 bxc4 28. Qxc4 Qxd5 29. Nxg6 Qxc4 30. Rxc4, when black will have succeeded, in part, but white threatens Nxe7, after which the connected, passed f- and g-pawns will tell:

Instead, MVL released the tension with 25. cxb5, offering meager resistance as Firoujza counter-punched in the center of the board:

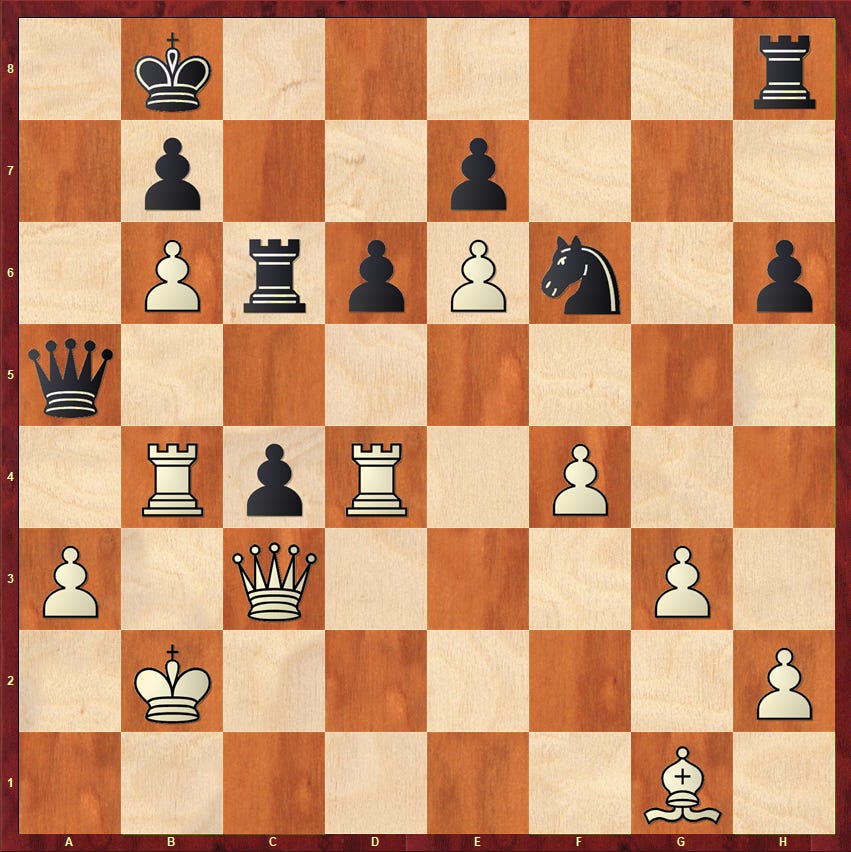

cxb5 Qf5 26. b6 Nxd5 27. Nh4 c4?! (Hard to tell what’s wrong with 27. … Qh5!?) 28. Qf3 Qf8 29. Nxg6 Qe8 30. Nxh8 Qa4+ 31. Kc1 Rxh8 with the following diagrammed position.

Here black has made progress in the center, but white has not advanced on the kingside. Neither the f- or g-pawn is fully a “passed” pawn, and his pieces are not coordinated. Black is still down a pawn, but he has firmly seized the initiative and white’s king may be feeling slightly unsafe. I can think of few clearer examples of a player following through on a strategic imperative than this position. As early as move twenty-two, Firoujza recognized that he could suffocate slowly with a space disadvantage, or he could fight for the center AT ALL COSTS. With the benefit of hindsight, the investment of a single pawn seems a small price to pay for the initiative and an active, central post for the knight:

Rd4 Nf6 33. Rb4 Qa5 34. Qc3 Rc6 35. Kb2?

And this is, in all likelihood, the losing move. The b6 pawn could have been held with either 35. Qb2 or 35. Rd1, clearing a line for the g1 bishop. After 35. Kb2? black firmly grasps the upper hand:

In this position, Firouzja would like to play 35. … Nd5, forking queen and rook, but the undefended position of the h8 rook plays spoiler. 35. … Nd5? can be met by 36. Rxd5 Qxd5 37. Qxh8. So Firouzja prepares the fork by bringing the rook to the queenside, and the white queen is forced to step out of the potential knight fork, but allowing the c-pawn to push on:

… Rhc8 36. Qc2 c3+ 37. Ka2 Rxb6? Too eager to regain the material.

… Rxb6? allows white to disrupt black’s coordination with 38. Ra4 Qb5 39. Rdb4 Qd5+ 40. Ka1 Rxb4 41. Ba7+ Kc7 42. Rxb4

… Nd5! instead, and 38. Ra4 Qb5 when the d5 knight controls the b4 square, preventing liquidation of the major pieces and preserving black’s initiative.

But again, Vachier-Lagrave showed that he was not in top form at this event, meekly acquiescing with 38. Rxb6 Qxb6 39. Bf2 Qc6 40. f5 Qb5 41. Be3 Rc6? 42. h3 (42. Bxh6! is fine…) Qe5 43. Bf2 Rb6 44. Qxc3 Qxf5 and white resigned, unable to defend both his king, and the f2 bishop:

Well played, Alireza Firouzja! I found this game to be particularly instructive. 5. … Bd5? is a typical opening mistake, allowing white to develop a crushing space advantage and central control, and ultimately leading to the position after 22. Rb1, when black is faced with a strategic imperative to undermine white’s center. That he must sacrifice material to do so, I also find instructive, because the natural instinct is to avoid the loss of material in all but the most clear cut circumstances. In retrospect, and with the aid of silicon study partners, it’s clear: black will lose if he doesn’t sacrifice a pawn, so why wait?

As for the mistakes later on in the game, well - such things are to be expected in online rapid play. I find chess games without mistakes no more interesting than those with an element of human intrigue. Nobody would watch basketball if the players made every shot, and I can’t help but feel that chess is similar in that regard. Nevertheless, chess fans around the world will be hoping that Maxime Vachier-Lagrave can regain his form before the World Championship Candidates tournament is scheduled to resume on November 1st, in Yekaterinburg. Play was suspended due to coronavirus at the halfway point in March, when Maxime Vachier-Lagrave had been in excellent form, having earned a share of the lead by scoring 4.5/7 along with Ian Nepomniatchi. With 7 games to go, Caruana (World #2), Grischuk (World #6), Giri (World #10), and Wang Hao (World #12), who all have even (3.5/7) scores, will be looking to close the gap.

Of course, the ultimate winner of the candidates tournament will be faced with preparations for a match with world champion Magnus Carlsen, whose chess results in 2020 have been impressive even in the context of his unbelievably rapid ascent to the world title and almost unblemished record of professional success and accomplishment. So far this year, the reigning world champion and (dare I say) GOAT, Magnus, has: placed 2nd in the Tata Steel tournament, 1st in the Magnus Carlsen Invitational, 1st at “Clutch Chess,” 1st at the Steinitz Memorial, 1st at the Chessable Masters, 1st at Legends of Chess, 1st at the Grand Final of the Chess Tour, reached the semifinal of the knockout event at Linares, and now split first at the St. Louis Champions Showdown: Chess 9LX event. Nothing less than top form will be acceptable for the player who intends to challenge Magnus for the world title.

And as for Hikaru Nakamura, the first chess “e-Sports” star and twitch pioneer, it’s possible that his success in the online arena has totally supplanted his attempts to fight for titles over the board. Nakamura peaked at a rating of 2816 and a world #2 ranking in October of 2015, but his results have slipped ever since. He now finds himself ranked #18 in the world, with a FIDE elo rating of 2736, and an abysmal career record against the champ (1 win, 19 draws, and 12 losses). Nevertheless, his creative style and lightning fast reflexes have made him a wizard in Chess 960, rapid, blitz, and online bullet chess, which are all popular with twitch audiences. Now that coronavirus has brought the whole chess world online, Nakamura might feel that the game is coming to him, and his best is yet to come.

What is there to say to that but, “T-S-M! T-S-M!? T-S-M?! T-S-M?”

Puzzle of the Week #4:

But first! A solution to last week’s puzzle, which can be found here: Fire On Board!

Naroditsky spied 1. Bxf7!? Kxf7 2. Qh5+ Kf8 (2. … g6? 3. Qxh7+ Kf8 4. Bh6#) 3. Bd6+!? Bxd6 4. Qxa5, which ostensibly wins a pawn and a queen for two bishops. But he didn’t calculate quite far enough. After 4. … Re5! the white queen is trapped on a5, and the whole sacrificial combination is rendered irrelevant:

Unbelievable that this calculation was performed in a minute-a-side game. For those of you playing along at home: 1 point for spying the “point” of the combination, which unveils an attack on black’s undefended queen @ a5. 2 points for spotting the refutation, 4. … Re5!

Inspired by Naroditsky’s failed sacrifice, we have the following: In this position, black is considering the sacrifice 1. … Bxf2+! Is that sacrifice, “correct?” (h/t @NealBruceBC)

Email solutions to JensenUVA@gmail.com, or DM on twitter @JensenUVA. Don’t forget to like, forward, share, subscribe, whatever you do, do it!

And until next time, ARGH! SHAKHMATY!